In the third part of The Media Men, a series of articles celebrating the founding fathers of modern media, Mike Yershon takes us back to the creation of Carat, and the ambition to build Europe’s largest buyer of media.

Starting out

I had seen an American 1940s film on the BBC featuring a guy who needed to come up with an advertising campaign for the Farnhight Featherlite, a new car to be launched. He had his blank paper on a draughtsman’s board but the ideas would not come. Then, in the early hours of the morning before the crucial day when he had to deliver, it all came pouring out. At the age of 16, in the summer of 1959, having left school with no job and no prospects, this story appealed to me. So when kind people asked what I wanted to do, I told them “advertising”.

New entrants to the industry came from university or art college, or straight from school. This latter group generally entered the dispatch department as a messenger. My introduction came from the IPA, located in London’s Belgrave Square, exactly where it is today. The Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) ran a service through which member agencies let it know of vacancies. I was given the names of two agencies to contact. One was Erwin Wasey, Ruthrauff and Ryan, which had moved to new offices in Paddington, and the other was Colman Prentis and Varley (CPV) in Grosvenor Street. I got the job at CPV, and started in November 1959 at £4 per week.

After six months, a vacancy came up in the media department. There were six of us in dispatch, and the five ahead of me all turned the opportunity down. Media was not seen as being worth losing your place in the queue to a heady career progression toward account executive, via the production department. For me it represented an opportunity to get out of dispatch, and who knew where this might lead. There was also a pay rise of ten shillings (50 pence) per week.

The media department consisted of roughly 20 people, organised in three sections: press buying, TV buying and media statistics. My job was to be in media statistics. I had to fill in pink forms using figures from large green books, published each week by an organisation called Television Audience Measurement (TAM). These contained estimated audience numbers for TV commercials appearing in specific commercial breaks for our clients’ brands.

Commercial television had started in the UK four years earlier with one station in London. It had expanded to the Midlands and the north of England by the time I started filling in the forms. Press audience research was provided by the National Readership Survey and I was briefed by my boss to visit the offices of the Daily Mail, where there was an IBM Hollerith machine that could slice and dice the punched cards that formed the readership survey sample.

Over the next few years, media statistics was renamed media planning, and through various reorganisations of the media department I added press buying and TV buying to my role. In addition, I attended evening classes on statistics and economics. These were to stand me in good stead in later years – all education is good. I also took the specialist media examination set by the IPA and passed, gaining the letters AMIPA after my name.

After six years at CPV, I felt the need to move on and responded to an advertisement in Advertisers’ Weekly for a group media planner at McCann Erickson.

McCann

Advertising agencies are forever reorganising. At the time of my interview, McCann had the same structure in the media department as CPV had when I started there. So the role of a media planner, in the media planning section, really suited me. I got the job and gave CPV one month’s notice, aiming to begin at McCann in May 1965. To my great surprise, on joining I was told my role had changed to that of a media group head, with a press buyer and TV buyer reporting to me. At the age of 23, I had no experience of managing people but, with the supreme confidence of youth, I just got on with it.

My boss was the deputy media director, who had been promoted from a role as a media planner. He had never bought media. Nor had his boss, the media director, who had a background in research. At the time, many of the agencies had recruited media directors with a research background. In this context, my media planning background and understanding of research was very helpful. But I had also bought media. This was to be very important in the next development, which came when my boss left in 1967.

In a reorganisation, the media director offered me the job of head of media planning and someone else the position of head of media buying. It was nonsense to split planning from buying, and I told the media director how I felt. There was no debate as far as I was concerned and I handed in my notice.

He immediately offered me the job of media manager, saying that if I made a success of it within three months it would be made permanent. When the media director left in 1968, I was promoted to replace him and invited to join the board.

“I was trying to explain to the client how we felt his money should be spent and it just seemed the wrong forum”

From 1968 to 1972, McCann London had a remarkable streak of winning new business in competitive pitches. This propelled the agency into the top five in the UK. The media department played an important role as part of the full-service team. Our lineup for pitches was led by the chairman, followed by the creative director, then the research director, then the director of sales promotion and lastly me, representing media. We never had more than two hours in total and I learned to speak very fast. Media generally ended up with ten minutes.

I felt this was crazy. I was trying to explain to the client how we felt his money should be spent and it just seemed the wrong forum. In addition, there was pressure on the talent in our department, with the best people being offered jobs by our competitors at much more than they were earning with us. In particular, our head of television buying was poached by Media Buying Services at a salary greater than mine. I could not obtain the money I felt we needed for salaries and sufficient additional people to cope with the workload. Agency management instructed me that the media service could not be more than 10% of the agency’s total costs. I was given this figure as it was the amount the IPA said that member agencies spent on their media departments. By the end of 1972, I could not see a way out of the conundrum and prepared to leave the industry.

Looking back, the answer to the question, “Why did media become unbundled from creative?” is bound up with this issue. At the time nearly all agency income was generated by 15% commission paid to agencies recognised by media owner trade bodies. So 10% of the 15% meant the ceiling for the media service was 1.5% of spending.

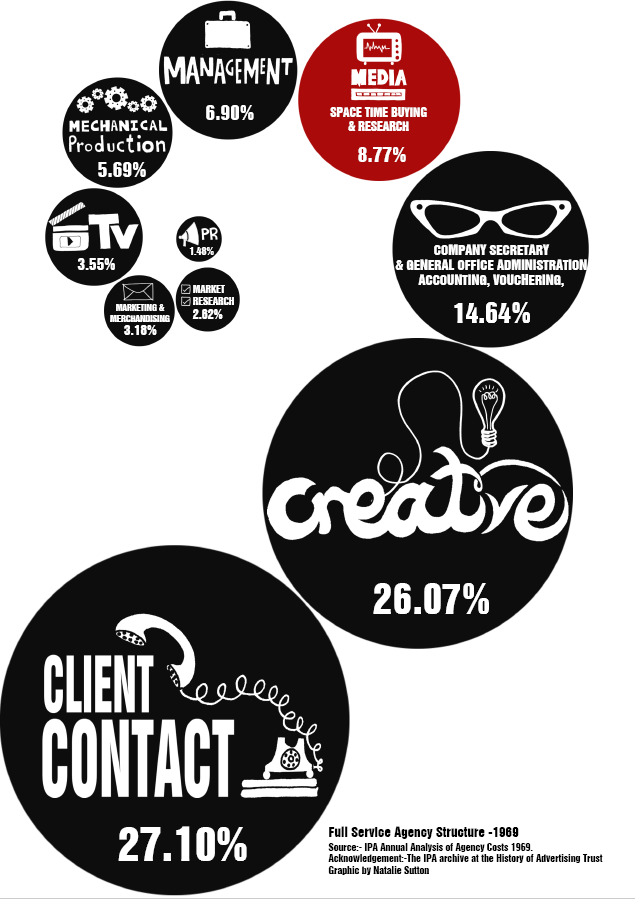

Once the media agencies in the UK had got under way, they were receiving the 15% commission as they had gained recognition. Roughly 12% was passed back to the advertiser to pay for the creative service. The media agencies were thus able to operate on double the margin available to their cousins in the media departments of full-service agencies. The graphic below shows actual IPA figures in terms of how full-service agencies in London were structured in 1969.

CDP

Early in 1973, McCann pitched for the Nescafé account against the holders Masius Wynne Williams and an English agency, Collett Dickenson Pearce & Partners (CDP), which happened to be located on the other corner of Howland Street.

CDP won the business and we were very disappointed. A few weeks later, I was asked to attend a meeting with the managing director of CDP. Initially I did not wish to meet him, as I was fed up with the way the agency business was treating media and saw no reason for CDP to be any different. But Frank Lowe said things would be different. He backed this up by agreeing to pay what it was going to cost to bring in the best people, in addition to the existing media department staff.

This allowed me to bring in Terry Alexander as a media planner and Steve Caras as a TV buyer, with both of whom I had worked at McCann. Steve had a friend, Alan James, who worked as a TV buyer at Grey and who also joined us. To complete the new top team, John Hewson from Foote Cone & Belding was hired as a media planner.

Within three months the media department was being talked about as the best in town. The agency was also seen as producing the world’s best advertising. This was a win-win for clients, and our business grew dramatically.

During this time, we drove two major developments. The first was in outdoor advertising. By 1975 CDP dominated the 48-sheet sector of the poster medium. To meet the service requirements of men across the country visiting each site and checking correct posting plus quality of visibility, we set up a joint venture with JWT. I became chairman and we needed a name. Sensitivities would not allow either agency’s name to come first, so our finance director came up with Portland Outdoor Advertising, as the offices were to be located on London’s Great Portland Street. Martin Sorrell (later knighted) bought JWT, and then JWT bought out CDP’s 50% shareholding. Portland was then merged with another big outdoor media agency and renamed Kinetic, which today is the largest outdoor media agency in the world.

“On the day my departure was announced, I received a call from a friend who was MD of Leo Burnett London. He wanted to see me for breakfast as soon as possible”

The second development was that we gained Reckitt & Colman Centralised TV Buying. To do this, we competed against four other large full-service advertising agencies, which each had a much greater share of that client’s expenditure than we did. By appointing CDP, the client chose to separate media from creative, a forerunner of the unbundling to come.

I spent four very happy years at CDP. The fifth year was not so happy, however, and I resolved to leave to set up my own business in media.

I had no financial backing as I did not know anyone who had money, so I arranged to remortgage the family home, which would provide sufficient funds to last three months.

On the day my departure was announced, I received a call from a friend who was MD of Leo Burnett London. He wanted to see me for breakfast as soon as possible. When we met at London’s Hyde Park Hotel, he produced a signed blank cheque and asked me to fill in the amount I wanted in order to join them. I figured that, with no offices, no staff and no clients, this sounded a good deal and it would give me the funds to set up on my own at a later date as long as I made a success of the job Burnett needed to revitalise their media department.

Leo Burnett

The role was vice chairman in charge of media, research and sales promotion, one of the top three people running the agency and reporting to the chairman. In the spring of 1978, media was going to be at the top of the tree in a large full-service agency. This was fine and only right.

One of my first tasks was to appoint a media director and I found a great one in Chris Dickens. I loved working with him to build the resource. By spring 1980, I felt my job had been completed and I could set out again on the path of starting my own business. I did not discuss the idea of the agency separating out media from their full-service structure as it was resolutely committed to the full-service way of working. I found offices above a shoe shop in London’s New Bond Street and opened the doors of Yershon Media Management on April Fools’ Day 1980.

Yershon Media Management (YMM)

When leaving CDP, I had had an idea in my head to enter the independent media sector in a different way to the others in the market. The idea was to offer consultancy to clients’ marketing directors in the strategic area of media planning. I would sit on their side of the table, working with their brand teams to develop a media planning brief. Then I would work with the agencies to help them develop the best solution.

Two years later, this still seemed a good way to enter the market. This time round I resolved to find offices as the first step, as I had the Burnett funds, which I calculated would last three months. If I ran out of money before gaining a client, I would have been content to look for a job as a media planner/buyer, feeling I had at least given it a go.

The offices were 500 square feet above a shoe shop in Bond Street, one of London’s most fashionable areas. In those days it took three months to obtain a phone line, so I used one belonging to my landlord. Letters were the other form of communication, and I started writing to the marketing directors of all the blue-chip advertisers.

I was fortunate to have my wife to help as a secretary, or the business would truly have been a one-man band. It was challenging but very exciting. A typewriter, two desks, a carpet, a meeting-room table and a car were all purchased with our scarce cash resources, and my phone calls produced one warm lead.

Keith Jacobs, the marketing director of Birds Eye, said I should speak to his secretary and fix a meeting. The first available date turned out to be six weeks later. No other warm leads existed when I met with Keith and his marketing managers, plus the head of marketing services.

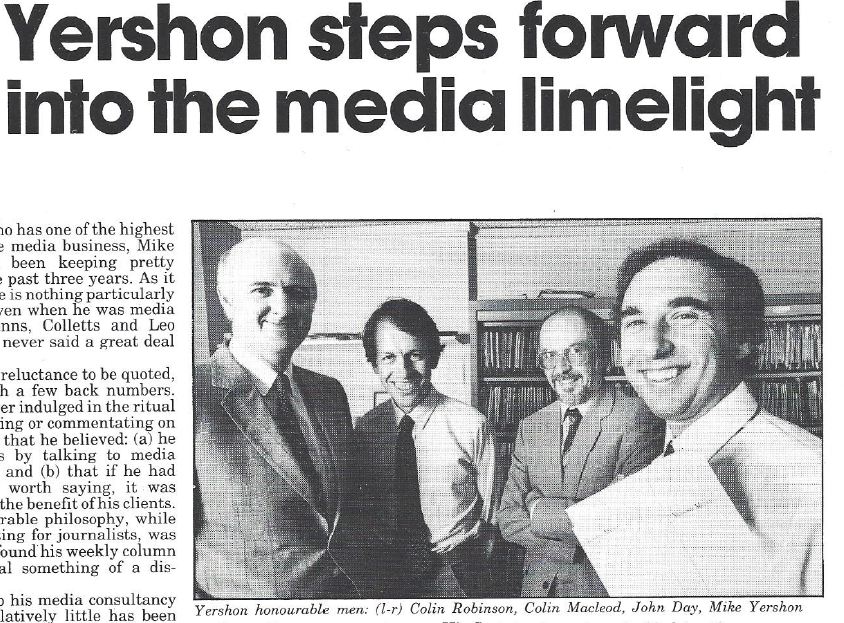

I felt the meeting went well, but time was passing, and we were getting close to running out of cash when the wonderful news came through that we had gained the business. My offering was new to the market and Birds Eye was seen as a blue-chip advertiser endorsing it, being a subsidiary of Unilever at the time. This represented a perfect start. It took another six months to gain the second and third clients, which were Seagram and Heinz. This meant I could hire our first senior executive, Colin McLeod, to be in charge of media research. I had met Colin at Burnett and he was prepared to give up his job as media controller of Schweppes to join the fledgling venture. Guinness came a few months later, and I knew I had established a proper business in media consultancy.

The Football League became an important client of YMM. We had been approached in our early days by the commercial director, who I had met when we worked for different agencies and shared the Austin Rover account. The brief was to help the commercial committee optimise the amount of money gained from the sale of non-theatrical rights to ITV and the BBC. We suggested the solution of taking two matches out of the Saturday 3pm kick-offs. One would be offered live to the BBC on Friday nights, and the other live to ITV on Sunday afternoons. This became the forerunner to all TV rights negotiations.

Yershon Media Buying (YMB)

I felt the need to extend into media buying, but this was not easy. There were plenty of buying competitors and I did not know their language, nor how the business model worked. I also wanted to continue growing in consultancy. The solution was to form a separate company from scratch, Yershon Media Buying (YMB), which launched in 1981. Two executives were hired – John Day from Gillette and Colin Robinson from Bates.

I would market the two companies under the Yershon Media banner, from the same offices with the same staff, and try to avoid client duplication. Buying clients would be offered the full consultancy service within the buying price. The buying company would gain 15% commission as recognised principals, and give 12% back to clients. They could pay for their creative services from the rebate. This strategy worked very well and our first buying client was Granada TV Rentals; this was followed by Coty perfumes, Olivetti, some business from Guinness mail order, and a new womenswear retailer, Next. Guinness awarded the buying company Harp Lager, along with a new product launch for a low-alcohol drink called Kaliber. The consultancy powered ahead, with business from Nationwide Building Society, Renault and ASDA, and more business from Unilever.

In 1985 the consultancy was awarded a piece of development business by Peter Wood. The brand was Direct Line Motor Insurance, and it was taking full pages in the Daily Mail. Response was not considered good enough by Peter and he was put in touch with me by a former Guinness client of mine who had joined a PR company. The agreement was that the ex-Guinness guy would invite Peter and me to lunch and, if we were getting on, then leave. Well, we got on famously. Peter became a client of the consultancy on a fee of £5,000 per month with an agreement that he would switch to being a buying company client when spending grew to over £2m.

“We were good, but I felt the buying market would move to scale, and we were too late into the buying market to compete on a scale basis”

In 1988 things changed in our world. Zenith had been created and TMDH had gone public. We were good, but I felt the buying market would move to scale, and we were too late into the buying market to compete on a scale basis. By this time, YMM was turning over more than £1m per year in fees. YMB’s £20m billings delivered nearly £600,000 a year and our profit was around £300,000 a year. Profits had stuck at this level and I was not confident they would grow to allow us to float on the stock market.

When I was approached by David Reich, the head of TMDH, to have lunch, I knew what was coming and, after much gum-sucking, it was clear that the best option was to sell. TMDH had been started by Chris Ingram as ‘The Media Department’ in 1972, pulling together the media function from a number of full-service agencies owned by KMP, where he was media director. When Chris left in 1976 to set up CIA, his own company, David Reich took over. David and his colleagues built the business from there, including buying it out from KMP. I got on very well with David and looked forward to the next stage of the journey.

Selling to TMDH and helping to create Carat

The deal involved my joining the public company board and keeping the two Yershon companies going during a three-year earn-out period. We sold on my wedding anniversary, 30 August 1988, for a mix of cash and shares in TMDH.

At my first PLC board meeting, David announced he had been approached by WCRS, who wanted to create Europe’s largest buyer of media, under the Carat brand name. WCRS was a full-service advertising agency, led by Peter Scott. Peter had completed an audacious 50–50 deal with Gilbert and Francis Gross, who had built Carat as a very successful independent media agency in France. For us, it involved a deal to sell 29.9% of TMDH. The deal was done in the knowledge that, if all went well, there was the possibility that an offer could be made in the future for the whole of TMDH.

The next three years involved continuing to grow Yershon Media and helping to set up the UK arm of Carat. Peter Scott had created an umbrella public company, with the Gross brothers as important investors, to hold a number of subsidiaries, including Carat. This was called Aegis. David Reich joined the board of Aegis with responsibility for Carat as COO. To me, this meant David’s focus shifted from the UK, as he was required to build the Carat brand in other markets. In 1991 Aegis bought the remaining 70.1% of TMDH.

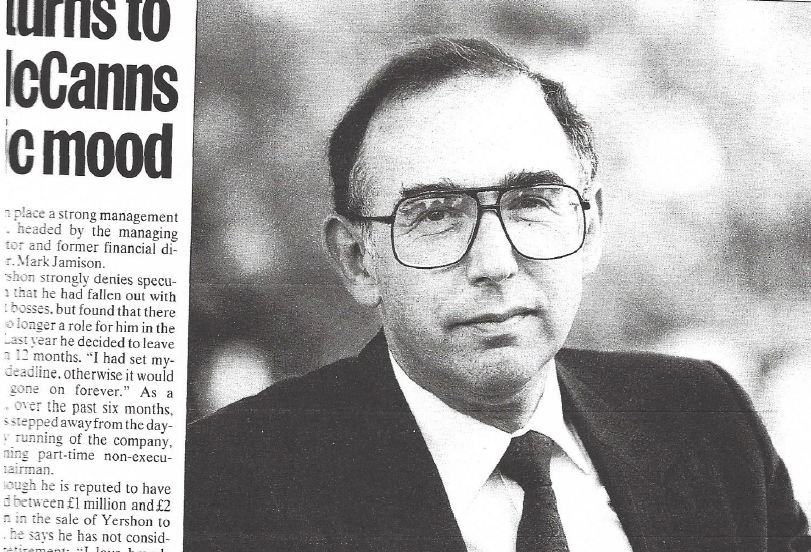

My agreement was that I could exit if control passed from TMDH, and in 1992 I resolved to do this. By an amazing coincidence, I received a call from McCann, which wanted me to go back, nearly 20 years after leaving.

McCann for the second time

It was eerie.

McCann was in the same offices, the media department was on the same floor, and the clients were broadly the same (with the important additions of Nescafé and Coca-Cola).

Media was under threat from the independents and my job was to reinvigorate the full-service offering. I relished the task, and set about reorganising and improving the motivation of the media department. An interesting piece of learning was that two of the three people I decided to promote were women. There had been very few women who had made it to the top in media and I could see things were going to change. All three became great successes, and Andy Jones went on to hold the top media job at IPG in the UK.

By late autumn 1993, it was clear that my job was done, and I did not wish to stay at the coalface a moment longer than needed. At the time, the big multinational agencies were clinging to full service. I still felt the idea was flawed, but did not fancy taking on the might of McCann from the inside. So I left McCann at the end of 1993 to start a new career, working from home and keeping my hand in the industry I love.

My first client was Peter Wood at Direct Line. We had kept in touch and, when I called asking if there was anything I could do, he said the timing was good as he was taking the company into financial services. Thus began a 20-year new career below the industry radar. Amongst many other things, this has given me the freedom and time to develop an understanding of the new media and encouraging the founders of our wonderful industry sector to tell their stories.